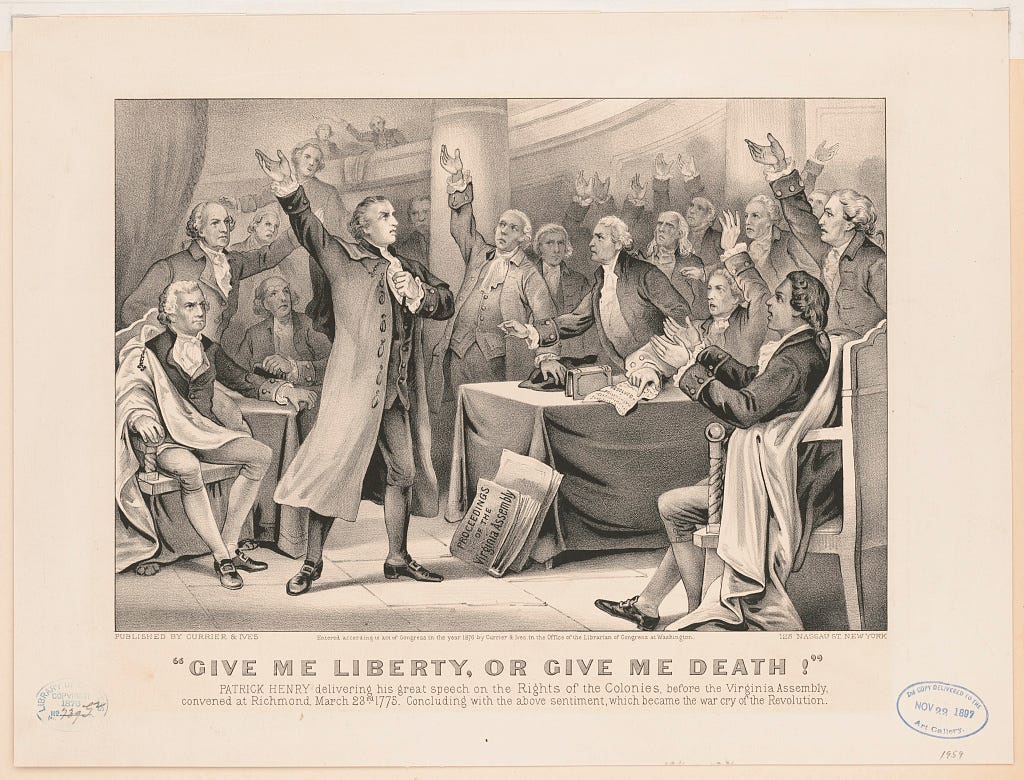

On 23 March 2025, the United States marks 250 years since the statesman Patrick Henry (1736-1799) delivered a speech before the Virginia Convention that he concluded with the now immortal words: “...give me liberty or give me death!”1 A sense of definitive culmination and epochal inevitability sharpens this enduring ultimatum, which Henry himself characterised less as a call to arms in preparation for a potential confrontation than as a battle cry in the midst of an unavoidable conflict that had in essence already begun.

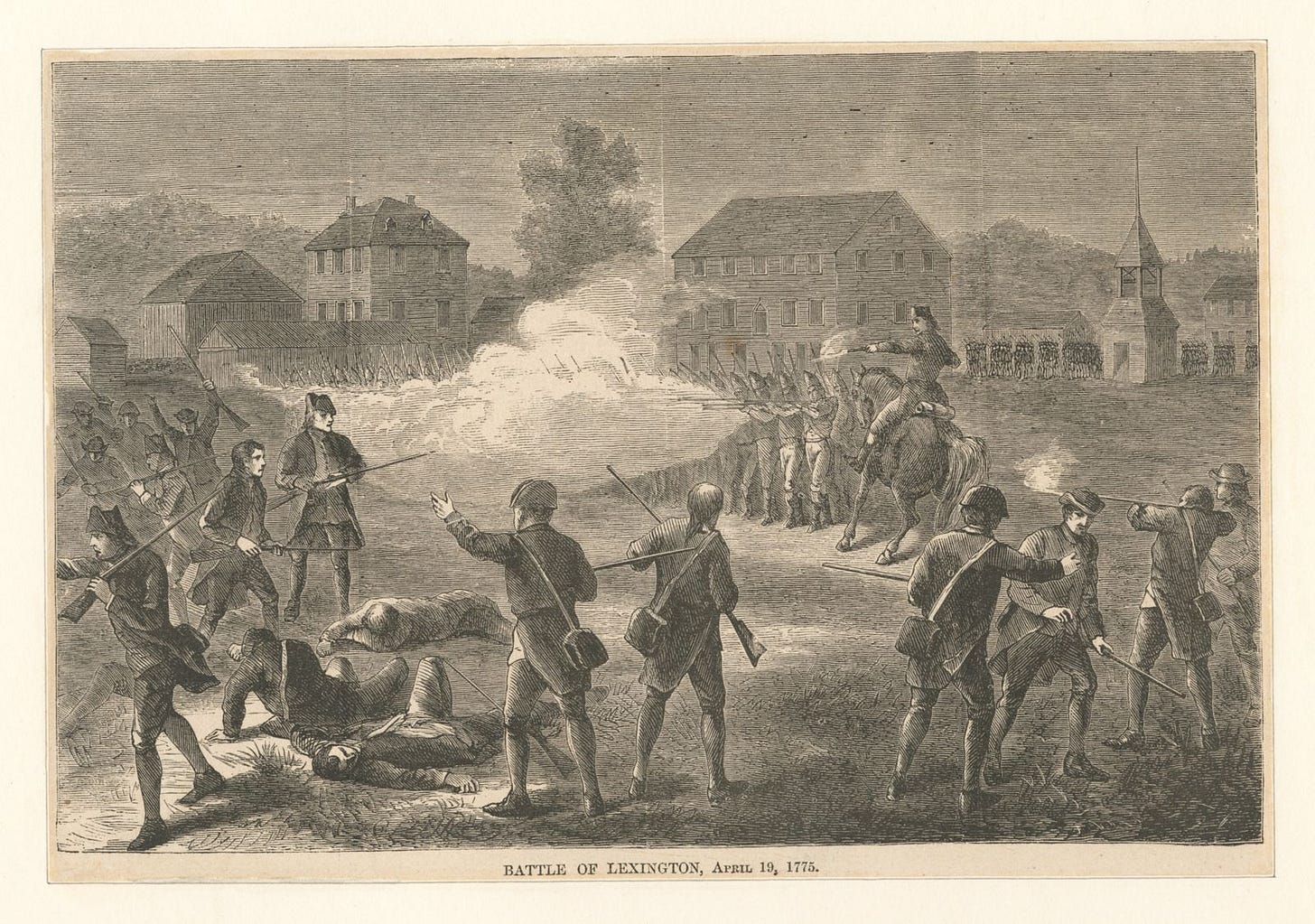

The first direct battles of the American Revolutionary War would take place a little less than a month later at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts on 19 April 1775. The circumstances of these engagements would eventually be memorialised in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Hymn, which was performed at the completion of the Concord Monument in 1837:

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled,

Here once the embattled farmers stood

And fired the shot heard round the world.

Commencing a fateful war that promised either ‘liberty or death’, the ‘shot heard round the world’ captures the singular drama of these early skirmishes, portending the existential stakes and the disruptive global reverberations of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Both phrases also allude to a formidable degree of focus, direction, and decisiveness embedded within both the ideological and quotidian origins of the American Revolution.

Emerging from a potent alchemical mixture of radical ideas, political manoeuvres, cultural dispositions, and material interests, the Revolution reflected a concerted effort to break away from the past and chart a new course towards liberty, republicanism, and democratic representation. In this way, the initial sparks of ideological struggle ignited what Jonathan Israel has described as The Expanding Blaze, which serves as the the title of his 2017 book on the incendiary radicalism of the Revolution and its enduring ramifications for global modernity.2

At the same time, the events surrounding Patrick Henry’s speech, as well as the circumstances of Lexington and Concord, reveal some of the ways in which history is always partly the product of contingency, accident, doubt, and uncertainty. Indeed, one of the many lessons of the American Revolution is that there is much to be gained from confronting and even embracing the unknown.

These features of the revolutionary mindset are evident in the writings of John Adams (1735-1826), a Massachusetts lawyer and Founding Father whose support for Bostonian resistance to British imperial dominance was tempered by his grave seriousness about the uncertainties that accompanied such defiance. A multi-layered study of criss-crossing connections at play during the period, Alan Taylor’s American Revolutions features a letter that Adams penned to his friend and colleague Jonathan Sewall in Spring 1774. In the letter, Adams explained that “Great Britain was determined on her system, and that very determination determined me on mine”, adding that in making such a commitment, he “had passed the Rubicon; swim or sink, live or die, survive or perish with my country”. This decision, he said, was his ‘unalterable determination”.3 Consider these remarks alongside a poignant excerpt from Adams’ diary written in June 1774, cited in David Reynolds’ Empire of Liberty, a sweeping epic history of the United States. In the entry, Adams expressed concern that, “The objects before me are too grand and multifarious for my Comprehension. We have not Men fit for the Times. We are deficient in Genius, in Education, in Travel, in Fortune — in every Thing. I feel unutterable Anxiety.”4

Recognising the coexistence of unalterable determination and unutterable anxiety in the minds of the American revolutionaries begins to capture the gravity of their situation and the burden that they had undertaken. These sentiments were palpable in Patrick Henry’s oration and seem to have been in the air at Lexington and Concord.

It is worth returning to Henry’s speech in March 1775; specifically, the famous final sentence, which reads in its entirety: “I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!” Historians continue to investigate whether the extant versions of this speech, published decades later, represent a verbatim textual reproduction of Henry’s words. This ongoing discussion itself suggests the productive role of uncertainty in retelling the history of the Revolution.5 Nevertheless, the speech marked a pivotal intervention in an unresolved debate. It reportedly swayed the convention, encouraging delegates to vote in favour of committing soldiers from Virginia to the wider cause of colonial resistance against the British Empire.6 It is understandably celebrated as an impetus for decisive action and an expression of unwavering commitment. Yet, as a rhetorical gesture towards speaking and acting for oneself, it also reflects a tacit awareness that each person had to assume the monumental risks associated with the revolutionary cause without knowing where the path would lead or who might join them along the way.

The exchanges of fire at Lexington and Concord in April 1775 similarly convey the mixture of conviction and contingency that characterised the early onset of the Revolutionary War. Ordered to arrest Patriot leaders and confiscate supplies of weapons and ammunition that colonists were illegally accumulating, a force of British Redcoats advanced to Lexington, where a group of local militiamen awaited them. When the British addressed them, the militiamen initially began to disperse, but refused to lay down their arms, at which point gunfire broke out. There were eight American fatalities along with ten more wounded. The militiamen eventually fell back and the British marched on to Concord, where further fighting took place. Militiamen prevented Redcoat efforts to cross the Concord River in pursuit of the armaments. The Redcoats were rerouted to Boston, suffering further guerrilla assaults at the hands of the Patriots along the way.7

The first battles of the American Revolutionary War at Lexington and Concord unfolded at a time when resentments that had simmered for years were catalysing increasingly pronounced expressions of defiance and sophisticated acts of resistance, as well as growing unity of purpose. Yet, even as advocates of a war for independence argued that the die had been cast, they did not pretend to know whether liberty or death lay ahead. This would be revealed soon enough, beginning with incremental provocations over the course of a single day, during which people on each side of the conflict found themselves caught between flinching and unflinching until it became clear that there was no looking away and no turning back.

James D. Hart and Phillip W. Leininger, The Oxford Companion To American Literature (6th edn, Oxford, 1995), p. 286.

Jonathan Israel, The Expanding Blaze: How the American Revolution Ignited the World, 1775-1848 (Princeton, NJ, 2017).

John Adams quoted in Butterfield et al, Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 1:137n5, cited in Alan Taylor, American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804 (New York, NY, 2016), p. 131.

John Adams, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. II, Diary, 1771-1781, ed. L. H. Butterfield (Cambridge, MA., 1961), p. 97, entry for 25 June 1774, cited in David Reynolds, America: Empire of Liberty (London, 2009), pp. 61-62.

John A. Ragosta, ‘“Caesar had his Brutus”: What Did Patrick Henry Really Say?’, Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 126 (2018), pp. 282-297.

Charles L. Cohen, ‘The “Liberty or Death” Speech: A Note On Religion and Revolutionary Rhetoric’, William and Mary Quarterly, 38 (1981), pp. 702-717.

Taylor, American Revolutions, pp. 132-133; Reynolds, America, pp. 62-63.